Wire fraud is one of the most frequently prosecuted white collar crimes in federal court.

Federal prosecutors often rely on wire fraud to prosecute cases when more specific crimes such as health-care fraud or bank fraud do not apply. In some fraud cases, the government will begin an investigation as possible wire or mail fraud and bring other charges once it learns more about the case.

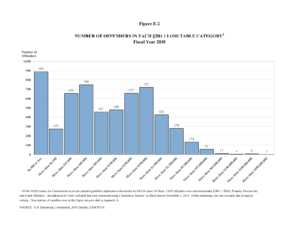

See the US Sentencing Commission’s 2018 Sourcebook here and the specific chart here.

What is wire fraud?

The federal wire fraud statute is 18 U.S.C. § 1343, it provides the wire fraud definition. To convict on wire fraud charges, the government must prove that the person intentionally used some kind of electronic communication, such as a phone or email, for purposes of committing fraud. The specific definition of wire fraud is established by its legal elements. These are:

- Scheme or artifice to defraud. This element requires the prosecution to prove that there was a scheme or plan to cheat somebody of money or something else that has value.

- The scheme involved false representations that were material. The prosecution has to prove that false statements were made. This can also include half-truths. But, these false statements also have to be “material,” which means they have to be capable of influencing somebody. (We provide an example of how this might work below).

- Intent to defraud. This requires the prosecution to prove that the false statements were made with the purpose to deceive, and not for some other purpose. (Read on to see an example).

- Wire transmission in interstate or foreign commerce. This requires the prosecution to prove use of an interstate wire—which would include internet, but could be any other wire transmission like radio, television, or a phone call. Because federal prosecutors do not have jurisdiction to prosecute state crimes, this establishes the interstate element that gives them jurisdiction over these offenses. Note that every wire communication can be a separate count.

One important detail often missed by educated laypeople is that the prosecutor does not need to prove the wire communications were themselves false or fraudulent. So long as the electronic communications were used as part of the fraud, the government can bring federal fraud charges and prosecute the crime as wire fraud. In an era of email and cellphones, only in the rarest of cases will the government have any trouble proving that wire communications were used in some way to carry out an alleged fraud.

Another thing to know is that the prosecution does not have to prove that the scheme was successful, or that anyone actually lost money as a result of it.

But this does not mean that there are no defenses to wire fraud. To learn more about these defenses, read on.

Who Investigates Wire Fraud?

Wire fraud is investigated by one of the many federal law enforcement agencies such as the FBI or any number of lesser known agencies. In some cases, multiple agencies stage a joint investigation. For example, the FBI might investigate the principal fraud while the IRS Investigative Division investigates related tax crimes.

In any investigation, there are a variety of law enforcement techniques that may be used. These could include subpoenas, search warrants, witness interviews and even wiretaps.

Defenses to Wire Fraud

Many defenses are available. Cases are very fact-specific, so we only give some basic examples here. Going back to the “intent to defraud” elements, courts have recognized that you are not guilty of wire fraud if you honestly believed in the statements or representations that later turned out to be false. This is sometimes referred to as the “good faith” defense.

Also, like bank fraud, the government must prove that the alleged misrepresentations were “material.” So, for example, let’s say there is a real estate purchase loan, like in mortgage fraud cases, and the wire fraud charges involved lying about income. The FBI investigates this suspected wire fraud case and finds that you exaggerated your annual income by $500. This likely would not be a material misrepresentation. Of course, real cases are usually not so simple, and it is important to have a white collar defense attorney carefully evaluate the case to determine if there is a “materiality defense,” and how to present it most effectively.

While federal prosecutors have jurisdiction over international and interstate wires, this does not mean that they can bring these charges in any federal court they want. There are requirements in federal cases for something known as “venue,” meaning a connection of the wire transmission to the state where the federal wire fraud prosecution is brought.

Numerous other defenses may apply, depending on the facts of a given case. If you are facing fraud charges, or being investigated for fraud, a federal fraud lawyer should review your case to advise you of any defenses that you might have.

Charges Related to Wire Fraud

The federal government often investigates wire fraud in connection with other offenses, and sometimes brings these charges in connection with other crimes. For example, mail fraud, bank fraud, health care fraud, and even bribery are often prosecuted alongside, or instead of, wire fraud. If more than one individual is involved in the alleged scheme, the federal government commonly brings conspiracy charges as well. More about these below.

State authorities can also bring charges of their own. Even if you are already indicted, the government can often bring a new indictment (called a superseding indictment) in the middle of a case, with different charges than the first. Each case is unique and it is important to examine your case closely to determine which charge or charges the government is likely considering and whether it has the evidence to prove them.

Other charges often implicated in wire fraud investigations or prosecutions include:

- Internet crimes

- Embezzlement

- Credit card fraud

- Identity theft

- Email crimes, phishing or hacking

- Tax fraud

- Securities fraud

- Money laundering

- False statement in a bank record

- Immigration document fraud

- Conspiracy

What is a Wire Fraud Conspiracy?

If more than one person is involved in the alleged wire fraud, federal prosecutors will often bring conspiracy charges as well. The laws used to prosecute these conspiracy charges are 18 U.S.C. § 371 and 18 U.S.C. §1349. In the most basic terms, conspiracy charges require the prosecution to prove that two or more people agreed to commit a wire fraud offense, and that the defendant joined in that agreement.

We discuss more about conspiracy charges in a separate article, but here is what you need to know as it relates to wire fraud: Prosecutors love conspiracy charges, if they decide to charge someone, as a general rule they will bring conspiracy charges whenever possible. This is for a few reasons.

One reason is that conspiracy charges make an individual responsible for all “reasonably foreseeable” acts of the others involved. So, even if the defendant did not do a specific act herself, she could be responsible for it anyway. This increases the risk of going to trial, because the acts of other members of the conspiracy can lead to a higher sentence. We explain why this is below.

The other reason is that in conspiracy cases, federal prosecutors can take advantage of certain evidentiary rules to bring in more evidence. This includes using the hearsay statements of anyone alleged to be a “co-conspirator” even if those statements would not otherwise be allowed into evidence. This also allows prosecutors to use the acts of co-conspirators. Let’s see how this works in practice.

Let’s say Smith and Jones are charged with conspiracy to sell counterfeit “precious” coins. Smith is the mastermind behind the idea, and he finds the customers using the internet, and talks to customers by phone. Smith sends customers fake certificates for coins by email, to get them to believe that they are previous antiques. Smith then sells customers the coins for a high price, when in reality they are worthless. Jones is a craftsman and makes the fake coins, for which Smith pays him a salary.

If Jones knows about Smith’s scheme, he will be criminally responsible for Smith’s acts, including the financial harm (called “loss”) to victims at sentencing. Even if he does not know all of the details, Jones will be responsible for anything that he could have reasonably foreseen that Smith would do.

Let’s also imagine that Jones is extremely careful because he does not want to get caught and go to prison for wire fraud. He does not talk to anyone. But Smith is a big-mouth. He wants to recruit Johnson to help with the scheme, and in doing so, he brags to Johnson over the course of many emails about how genius and successful the scheme is, and how great Jones is at creating counterfeit coins. These statements would be allowed in at trial not just against Smith, but also against Jones. And they would come into evidence against Jones even if Jones did not know Smith had made them.

It should now be clear why conspiracy cases give prosecutors a massive advantage. If a prosecutor had little evidence of Jones’ guilt, using Smith’s statements and acts allows that case to be much stronger.

As with substantive wire fraud charges, conspiracy charges also have a number of potential defenses. This in itself would be a long discussion, and we do not get into it here. But from the simple example above, it should be clear that for those charged with conspiracy, it is important to have a lawyer who knows how to fight conspiracy charges.

Wire Fraud Penalties and Sentencing Guidelines

Wire fraud and other financial crimes can carry long prison terms even for people with little or no criminal history. Both offenses carry a wire fraud penalty of up to 20 years in prison. In reality, the sentences in wire fraud cases are determined by a close analysis of the facts of the case, and the background and character of the person that is before the court for sentencing.

The federal sentencing guidelines are, by law, the starting point for the judge’s consideration. They are advisory, but play an important role in determining what sentence may be imposed, even if it is only setting a baseline for the ultimate sentence.

Fraud sentencing can be a complex, and what we provide here is a very general overview, intended to give a very basic glimpse into the nature of the beast. Every case will have unique facts and nuances, and needs to be evaluated by an experienced attorney.

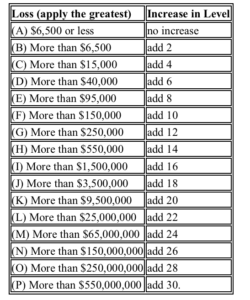

Wire fraud cases usually, but not always, fall under sentencing guideline § 2B1.1. That guideline provides a number of factors about the offense conduct that can push the offense level up. One of these factors, often the most critical, is the amount of “loss.” The table below shows just how much of a role the loss calculation plays. (The numbers on the right are “offense levels” which correspond to greater and greater ranges of suggested imprisonment.)

See the full sentencing guideline here.

Typically, “loss” will mean loss of money to a victim, but not always. In some cases, there will be no loss to victims, and indeed there may be no “victim” at all. In these cases, prosecutors will rely instead on the “gain” to the defendant, or something called the “intended loss.” The loss calculation, and even the basic question of whether there is any loss at all, is often a topic of intense dispute between prosecutors and defense lawyers. As you can see from the table above, the loss component can have a profound impact on sentencing, and often means the difference between probation and prison.

Many other offense characteristics can also increase the advisory sentence, for example:

- The offense involved multiple victims;

- The offense caused “substantial financial hardship”;

- The offense involved a “misrepresentation that the defendant was acting on behalf of a charitable, educational, religious, or political organization, or a government agency”;

- The offense involved a “misrepresentation or other fraudulent action during the course of a bankruptcy proceeding”;

- “A substantial part of a fraudulent scheme was committed from outside the United States”;

- The offense involved “sophisticated means and the defendant intentionally engaged in or caused the conduct constituting sophisticated means.”

In addition to the fraud guideline, there are other sections of the sentencing guidelines that may apply. For example, section 3B1.1 through 3B.5 provides for certain enhancements or reductions for the defendant’s role in the offense, such as abuse of a position of trust or a special skill, leadership versus minor role, and others.

The above is just a small sampling of some of the factors that can drive up the advisory guidelines range. As with loss, the question of whether these enhancements actually apply can be nuanced. Frequently, there will be strong arguments that offense characteristics do not apply. These battles over the offense level must be fought vigorously, because the advisory guidelines range is typically important to the sentencing judge.

But the correct calculation of the sentencing guidelines is only the beginning. After this is done, the judge will then consider many other factors under 18 U.S.C. § 3553. This requires the judge to consider things like the nature of the offense, the background and character of the defendant, the need for deterrence, the need to protect the public, the kinds of sentences available, the need for treatment, and virtually any other factor. This is also where judges will consider arguments about whether the guidelines fairly reflect the seriousness offense and/or the defendant’s criminal history, and if not, why not. To get a more in-depth understanding of the federal sentencing process, check out our article on the subject.

In the era where the guidelines are no longer mandatory, evidence about these other factors can play a profound role in the outcome. Here are some key statistics:

- According to the US Sentencing Commission, the average sentence for fraud, theft and embezzlement offenses was 23 months for fiscal year 2018. See Table 4, US Sentencing Commission 2018 Quarterly Data Report.

- In fraud, theft, and embezzlement offenses generally, judges imposed a downward variance (a sentence below the guidelines) much more often than they did an upward variance. Specifically, in fiscal year 2018, out of a total of 6528 sentences, judges imposed 2118 downward variances, and only 110 upward variances. See Tables 10, 14 and 18 of the US Sentencing Commission 2018 Quarterly Data Report.

- For Fiscal year 2018, the average downward variance in this class of cases was 15 months below the guidelines.

- Roughly one out of six individuals charged with fraud in fiscal year 2018 received a sentence of probation. See U.S. Sentencing Commission’s 2018 Quarterly Data Report, Table 7.

These statistics, particularly the second and third bullet points, tell us that judges are willing go below the guidelines in fraud cases—and often significantly below—if presented with effective arguments and compelling facts at sentencing.

Talk to an Experienced Fraud Attorney

If you believe you may be facing such charges, it is important not to discuss your case with anyone (especially the government) before speaking with an experienced federal white collar crime attorney. If you would like to discuss your case with us, please use the contact form to set up your free consultation.